How can we… use AI to support clinical decision-making in intensive care?

19 February 2026

Radzim Sendyka, Research Assistant, Department of Computer Science and Technology, Accelerate Programme for Scientific Discovery

19 December 2024

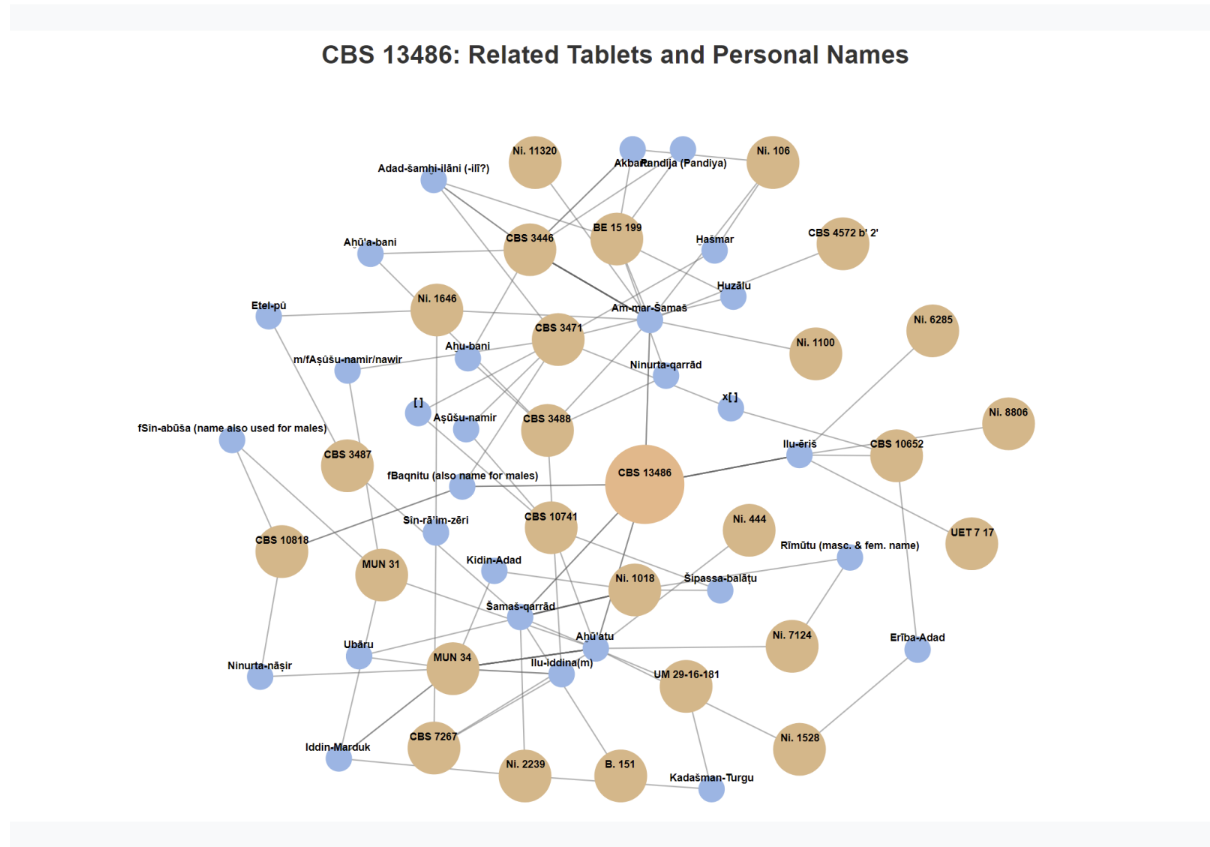

Above image shows graphical representation of connections between tablets and personal names, presented in the user interface. Yellow nodes are ancient tablets, connected with blue nodes representing the people who lived during that time, and are mentioned in the tablet texts.

Assyriology helps us understand the cultures of ancient Mesopotamia, one of the world’s earliest civilisations, which changed the course of human history. The field is based on the study of texts etched into cuneiform tablets - clay artefacts carrying writing made using wedge-shaped impressions between 3,000 and 4,000 years ago.

Resources such as the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative and the Middle Babylonian Text Dataset have made efforts to catalogue and understand Assyriological data. However, digital repositories are sparsely populated, non-standardised, and poorly interconnected, meaning they are difficult to use for the global research community. There is a unique opportunity to catalogue and organise the majority of our knowledge about a civilisation into a single dataset and leverage computing resources and data science methodologies to answer questions that require simultaneous insights from the entire dataset, or implement currently used methods to perform them in a fraction of the time. In other words, it is providing Assyriologists with tools that can be used to speed up their work as well as potentially augment the scope of analysis available to them.

Interdisciplinary work requires multiple perspectives and on this project, I’ve been working with other members of the Accelerate team, Diana Robinson and Professor Neil Lawrence, and also Dr Jonathan Tenney, Assistant Professor in Assyriology at the University of Cambridge. We began with an aim to develop machine learning tools to advance research in Assyriology and reveal new insights that may not be available without tools from computer science. This is an ongoing project, the first part of which focused on data science, and further phases will incorporate machine learning.

Putting experts first

A key focus of this project is putting the domain expert at the heart of the process. For this, we used a set of methods from human-computer interaction – Diana Robinson led the fieldwork and qualitative analysis in this portion of the work. We began with ethnography and semi-structured interviews in which we observed Jon analysing tablets and the process of transliterating and translating them. He demonstrated how analysis of individual tablets was combined with his various sources of existing data to build an evidence base to answer his overarching research questions. We analysed the qualitative data from the ethnographic part of the work using grounded theory. This method was used to derive design principles that captured the essential nature of Jon’s work which we could then use to think about areas of fit with data science methods to augment his workflow. In contrast to structured and quantitative computer data, Assyriological knowledge is denoted and organised in human-centric ways where unquantifiable side notes and ineffable context are integral. The field is detail-oriented and values evidence-based assertions supported by previous research and data.

This made interpretability incredibly important, so we developed systems for automating visualisations and providing the textual basis for any relationships found. This allowed researchers to make assertions using their expertise to augment the rationale and exclude less-relevant factors.

Working with Dr Tenney, we developed evaluated tools using the Three Esses Framework, developed by my supervisor, Professor Neil Lawrence. We gathered, pre-processed and analysed data throughout the process, to understand its opportunities and limitations.

First, we focused on data about Middle Babylonian Cuneiform tablets gathered by Dr Tenney and additional data about cuneiform tablets from a longer period, provided by the Cuneiform Digital Library Initiative. We identified sources relevant to this project and augmented the dataset by creating new orderings of files to make accessing different data sources in the repository easier.

Dr Tenney’s involvement in this process enabled us to gather ‘hearsay data’ in the framework of Data Readiness Levels. We could then pre-process digital resources to arrive at machine-readable and analysable data. We designed repeatable procedures to fix problems. We fixed misspellings and recovered the original names and metadata of a huge set of pictures that had been corrupted. We found that dates were written in different ways and there are many possible spellings of Assyrian kings’ names and that converting them into a uniform system was challenging.

Clustering for new connections

Having accessed and assessed the data needed, we applied computational approaches to the problems of date prediction and tablet clustering, using a couple of different clustering methods for groups and general clusters. One of the main aspects of Assyriological work is understanding the context of tablets, people, and the relationships between them, which is not easy when evidence from the time is relatively scarce, and remaining cuneiform tablets are scattered in museums around the world.

Links extracted from the ‘Personal Name Index’, combined with those evidenced by Dr Tenney are particularly important. We optimised the process of finding relevant entries by combining and aggregating the links into lookup tables from each tablet with all names it references, and from each name to all the tablets in which it appears.

The program we designed can access information about the personal names on a tablet and can then determine other tablets where the same names appear. The data is visualised in several ways, including lists of names, graphs and interfaces that include pictures of tablets.

While the algorithms aren’t very complex, there are some computer science optimisations and neat dynamic programming tricks involved, and we went through wrong approaches before coming up with a successful program. For example, we could have taken the approach of systematically going through all the tablets, picking 5 to try and see what names they have in common, logging any commonalities and then comparing more, but the size of the data set means this would take too long.

Turning Dr Tenney’s methodology into code, we decided to use the program to compare and match pairs of tablets with to see if they have names in common. It combines information found in linked documents and personal names in a mathematically defined system to provide explainable estimates for the likely origins of tablets, making connections faster than a human can.

We demonstrated the accuracy of our system by making temporal predictions for tablets with known ground truth and assessing the distribution of measurement errors. Evaluation of our approach in field experiments showed that this method can give an advantage over current practices in the field.

We assessed the measuring the potential time savings made possible by the developed data entry tools with an average of 14% faster text entry. With a data set of up to 10,000 tablets and each tablet taking 3-5 minutes to input this time saving is significant. We showed that our methods have high accuracy and recall, while also being able of finding new potential connections which were previously unknown to researchers.

Using the program, Dr Tenney found that there are ‘clusters’ of people present across multiple tablets. This is a benefit, because while he has been able to identify some such groups in the past, he was not able to comprehensively search through the data available for all potential groups which fit these criteria.

Harnessing data science has allowed Dr Tenney to find new connections that he will explore. Hopefully, discoveries made using these results will be published soon.

Building on connections

Finding closely connected groups of people has implications for the field of Assyriology because the connections could signify the discovery of members of a family, people who belonged to the same working groups to shed light on their daily lives, or other types of relationships that provide new insights into the structures that existed during those times.

I hope to continue working with Dr Tenney. One continuing challenge in his field is the detection of missing tablets - gaps in the knowledge that could be caused by a missing tablet that once existed and may have been destroyed, not yet found, or not included in the current archives.

Working on this tool demonstrates what is possible via collaborations. I’m really happy that we can use computer science to solve research problems in other disciplines and hope to connect with other researchers to come up with simple solutions to help them with their work.