How can we… use LLMs to automate and optimise scientific workflows?

11 December 2025

Nina Haket, PhD student in the Department of Theoretical and Applied Linguistics

08 October 2024

The way we talk about concepts matters. It can cause social and political harm.

Philosophers worry that the way we use everyday language may prevent us from accurately portraying the world, or even undermine our ability to think clearly. I study conceptual engineering and am interested in changing some aspects of natural language that are problematic or defective. Perhaps they contain paradoxes or are ambiguous, which might have undesirable consequences in society. For example, defining ‘gender’, ‘woman’ or ‘minorities’ more broadly or narrowly can have a large impact on the people that fall into these categories. Conceptual engineering seeks to get to the core of an issue and then work out reasoned arguments for why a concept needs revision, which can be offered to a community for consideration. It’s unique because it aims to change language or concepts.

Changes in language can be difficult to analyse, but my approach uses Large Language Models (LLMs) to identify how words are used, drawing upon data from conversations between real people, and therefore taking a step away from introspective thinking about words.

Finding meaning in my research

I’m questioning what conceptual engineering is (as there are many views), how it relates to linguistic theory, and how the sense or meaning of words and concepts can change, or be changed. Determining the variations in a word’s sense or meaning in a particular context is word sense disambiguation. By using LLMs to identify how we actually use the words we might engineer, we can more comprehensively identify and address the issues it might raise.

Firstly, I’m creating a taxonomy of different kinds of words that conceptual engineering would affect in different ways. For example, we would not engineer the word ‘tree’ in the same way as we’ve tried to engineer the word ‘woman,’ but a lot of literature does not make this distinction, applying one framework to all sorts of types of words. So, I posit how we should be engineering with different expected outcomes on a semantic level and the methods we could use.

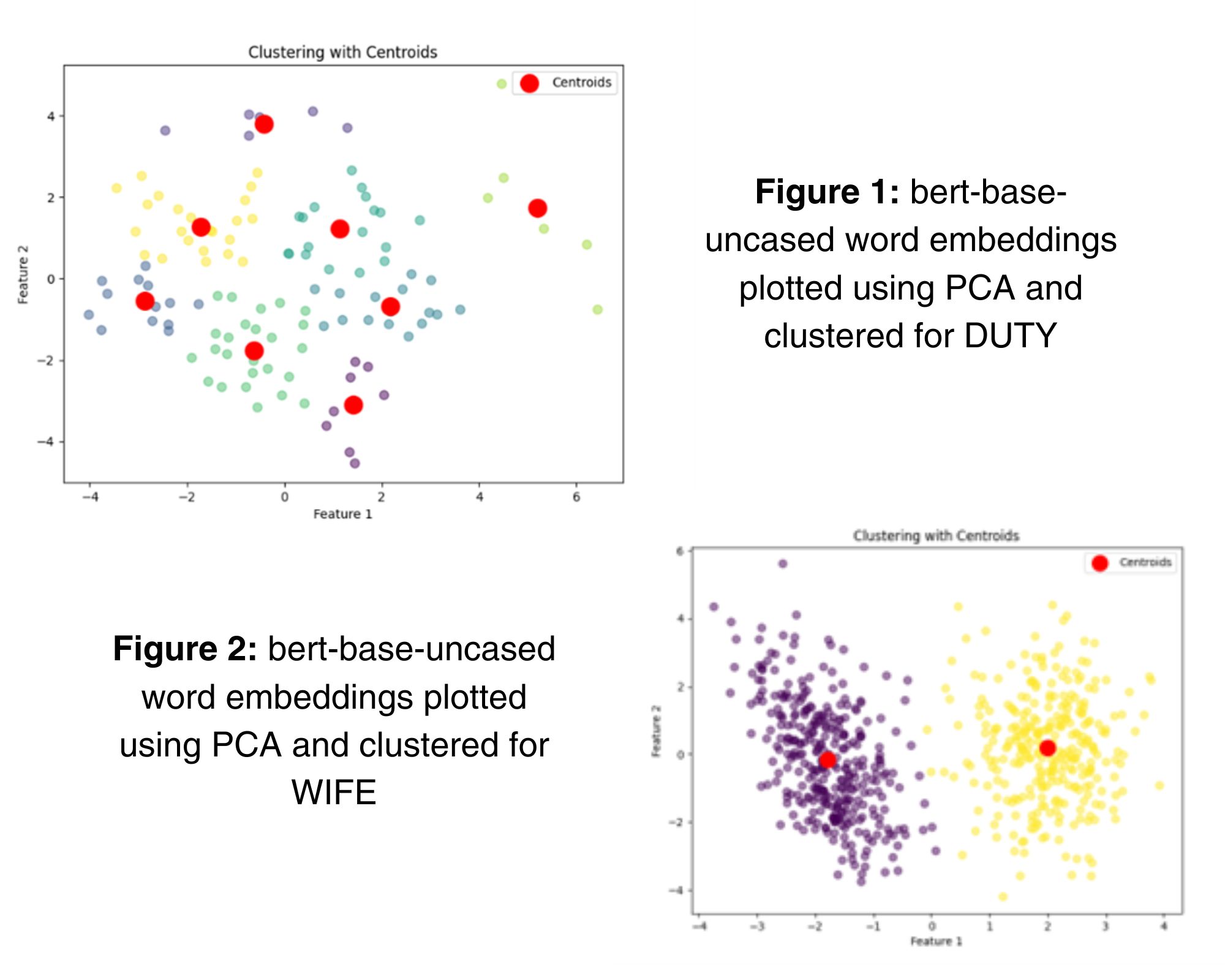

One of the challenges is that to change a word you have to understand how it is used in conversation. For example, colloquial use of a phrase like “Don’t be such a woman” is very different from how policy and legal representatives would use the word woman. I’m using an LLM, BERT, and the spoken component of the British National Corpus (a 100-million-word collection of samples of written and spoken language designed to represent a wide cross-section of British English) to create contextualised word embeddings for a selection of words that I’ve chosen including ‘theory’, ‘family’, ‘computer’, ‘data’, and ‘knowledge,’ to see how they are used in real life in real everyday spoken language. Currently I’m using bert-base-uncased, which is a tried-and-true method for semantics, but I’m experimenting with other LLMs too.

I’m interested to seeing whether the embeddings show any particular patterning when visualised, for example whether usages are tightly grouped into distinct senses, or whether there is a high degree of variability. Later in the project, I will start to consider whether this variation is due to the lexical content, or evidence of Pragmatic influence at the discourse level, and whether this is even a useful distinction to draw. I will use this to consider the theory behind conceptual engineering, and consider whether engineering words is practical or possible when we take into account all the variations in their usage and meaning.

Diagnosing problems with the AI clinic

I was attempting to do the code myself, but noticed that the word embeddings I was creating seemed to be missing some datapoints, or creating some very weird patterns when projected using PCA. I decided that to solve the problem, I would fine-tune bert-base-uncased on my data, since I thought the problem was being caused by the fact that the model might not be suitable for the spoken language, I was generating the embeddings on. However, I got completely stuck doing this. It was frustrating. Luckily, I found the AI clinic with a quick Google search.

Despite the fact that I went in with a problem concerning fine-tuning BERT, Ryan Daniels from the Accelerate Programme quickly noticed a problem with my initial code that was causing the issues, and not the lack of fine-tuning of the model. The code was not correctly transforming the contexts into something that the LLM could read, so there were were not enough points on the graph. With support from Ryan, I fixed the original code and since then, he has helped me add other implementations, such as metrics to measure the distance, and therefore difference, between different word embeddings.

The AI clinic has supported my work and has led to collaborations too. Ryan and I presented at a conference on LLMs and philosophy in Poland in May as well as at the Inter-Varietal Applied Corpus Studies (IVACS) conference in July. The field that I’m working in, and the application of these kinds of contextualised embeddings to conceptual engineering is relatively new, so it will be interesting to share our work at the conferences and see how others in my field are using LLMs in their work.

I’m currently taking a short break from developing LLMs and protocols to focus on the theoretical background in this area for my thesis. I’ve managed to do the taxonomy in lexical terms and I’m close to having a theoretical scaffolding around it that I’m happy with, so it’s going well.

Focusing on the future

Linguistics researchers studying semantics, conceptual engineering and philosophy are focused on language being creative and flexible, but tend to not use big data to analyse it. I hope to try and get more people using LLMs and data to back up their work concerning how the ways words are used have changed, especially in conceptual engineering. If it’s completely theoretical, it misses the point of the highly applied and human aspect of conceptual engineering but technology offers a way to test and analyse ideas, as well as potentially track how people use certain words over time.

Looking at how words have shifted over time using computational tools like LLMs is frequently done in linguistics. For example, the word ‘gay’ is now rarely used to mean ‘joyful’. Spoken language is usually not spotlighted in these studies, since we do not have data on spoken language spanning a large period of time yet. So, while the project is currently looking at describing how we currently use spoken language, it would be fun in the future to draw on how spoken language shifts over time when the data does become available with the help of LLMs. You could potentially look at the same words again over time and see precisely if they shifted and if their meaning has changed in the direction conceptual engineers were trying to nudge it, for example by becoming more coherent. If you saw that the clustering became tighter, then something must have changed in usage patterns and it would be fascinating to be able to track these shifts. For example, examining the word ‘virus’ in the BNC14 versus a more recent spoken corpus would give really interesting insights into how our concept of viruses have changed after the COVID-19 pandemic.

Check out the paper BERT’s Conceptual Cartography: Mapping the Landscapes of Meaning for more information.

Accelerate Science’s AI Clinic supports researchers at the University of Cambridge to support you in implementing machine learning at all stages of the research pipeline. Learn more about the clinic and contact us to find out how we can help.